Ralph Richard Armstrong was born on the 18th June, 1903 in the small village of Walbottle. At that time Walbottle was in Northumberland but later was incorporated into the city of Newcastle. Armstrong's father was the local blacksmith and few at Walbottle Primary School could have suspected the strange direction that his life would take.

At the age of 14 he started work in a local foundry and engineering works as a labourer. He moved to be an apprentice and was finally employed as a crane driver . At the end of the First World War Armstrong suddenly opted for a life at sea and joined the Merchant Navy. Again he worked his way up to to being a radio operator and served in many ships between 1920 and 1937. Between 1937-54 he also worked as a typist, a secretary, an architect's assistant and an undertaker's labourer.

His first book was "The Mystery of Obadiah" in 1942, but his greatest success was "Sea Change" which won the prestigious Carnegie Medal in 1949. Armstrong lived the latter years of his life in Somerset and died in 1986 after producing over 22 books for children. He also wrote under the pseudonym Cam Renton, the name he had assigned to his hero in "Sea Change".

Books

BOOKS FOR CHILDREN

The Mystery of Obadiah 1943

Sabotage at the Forge 1946

Sea Change 1948

The Whinstone Drift 1951

Wanderlust: Voyage of a Little White Monkey 1952

Danger Rock 1956

The Lost Ship 1958

No Time for Tankers 1959

Another Six 1959

The Lame Duck 1961

Before the Wind 1959

Horseshoe Reef 1961

Out of the Shallows 1961

Trial Trip 1963

The Ship Stealers (as Cam Renton) 1963

Island Odyssey 1963

Big-Head (as Cam Renton) 1964

The Greenhorn 1965

The Secret Sea 1966

The Mutineers 1968

The Albatross 1970

BOOKS FOR ADULTS

BOOKS FOR ADULTS

The Northern Maid 1947

Passage Home 1952

Sailor’s Luck 1959

Storm Path 1964

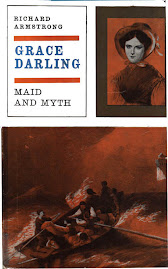

Grace Darling, Maid and Myth 1965

Centenary Article

"A life raft is found bobbing in the sea its sole occupant a young man suffering from exposure and shock. Gradually Judd’s incredible story is pieced together; it is a tale of adventure and conflict, and a runaway voyage in a stolen ketch.” As the writer of the blurb to Richard Armstrong’s “The Albatross” correctly comments it all makes a “gripping adventure story”. But perhaps even more remarkable is the story of Armstrong himself – a man who rose from a humble background to become the winner of the most prestigious prize for children’s literature.

Ralph Richard Armstrong was born, the son of a blacksmith, in Walbottle on June 18th, 1903, one hundred years ago to this very day. He went to Walbottle Primary School but left at the age of 13 to start work in a large foundry and engineering works (probably his namesake’s Lord Armstrong’s Elswick Factory). There he was a boy messenger, a greaser, a labourer and then finally a crane driver. At the end of World War One his career took a sudden jump in a different direction for he made up his mind that he would go away to sea. From 1919 to 1937 he worked his way up from deck-hand to radio operator, learning all that could about the sea and the men who sailed on it. Having “swallowed the anchor” he drifted through various jobs from typist and secretary to architect’s assistant and even undertaker’s labourer. And then the stories began.

First of all Armstrong drew upon his experiences as a boy in the lower Tyne valley with “The Mystery of Obadiah” and then as an apprentice in the great gun-making factory with “Sabotage at the Forge”. Even today you only have to read the latter of these two books to see that Armstrong had found his feet. Nowhere else in children’s literature is there such a good example of conveying the experience of young boys working in a complicated industrial environment. As such it ceases to be a mere adventure story (and a good one at that !) and becomes also invaluable evidence of our north-eastern industrial heritage.

But it was with “Sea Change” in 1948 that Richard Armstrong broke through to national and international recognition. It is a story of a boy coming to terms with maturity as he grapples with life on board ship ploughing its way from Liverpool to the West Indies. It won him the Carnegie Medal and, with a few exceptions, the rest of his career is devoted to tales of life on board ship. In 1955 his novel “Danger Rock”, a story of grim survival on an island off Newfoundland, won him the New York Herald Tribune prize and was reprinted in the U.S.A. under the title “Cold Hazard”. For younger children he wrote “Greenhorn” telling of the trials of a young apprentice who begins his first voyage at about the place on Newcastle Quayside where the Millennium Bridge now stands.

It is hardly surprising that a man with such a background should produce many stories about “Those who go down to the sea in ships” but it is extraordinary that he managed to retain such a high standard over so many years. His secret was to be both realistic and thought provoking at the same time. Thus “The Mutineers” (1968)is his own portrayal of the activities of a group of boys on a deserted tropical island and many critics have seen it as a plausible riposte to William Golding’s famous pessimistic “Lord of the Flies”. “The Albatross” with which this article began chronicles the disintegration of a band of thieves who have stumbled upon the treasure that is to destroy them.

The meagre details we have of his life tell us that Armstrong settled down to live in West Somerset, and indeed he died there in 1986. However, one only has to turn to “The Whinstone Drift”, his story about a coal mining valley in Northumberland, to realise that he had an intuitive understanding of certain aspects of northern life which he could describe in a way not equalled by any other local children’s writer, with the possible exception of Frederick Grice in his stories of the Durham coalfield.

Since Armstrong won the Carnegie Medal in 1948 there have been two other writers born locally who have matched this achievement. However, Robert Westall was born in Tynemouth and David Almond hails from Felling. Each one in his own way has written about the River Tyne but it is Armstrong who most truly belongs to Newcastle. In 2005 the Centre for the Children’s Book is to open in the Lower Ouseburn Valley not much more than a mile from where Armstrong sent his young hero (and himself) out to sea and where David Almond allowed his characters to drift on a raft in “Heaven Eyes”. In its mission to become a store-house of children’s literature and a research resource you can be sure that, though its brief is to be a national and international centre, it will not neglect its “local heroes” in the world of children’s literature.

On this day, one hundred years on from Armstrong’s birth, I wonder if Newcastle City Council could be persuaded to allocate a blue plaque to a notable citizen, to an unusual man whose children’s stories gained him an international reputation and whose local stories captured the very essence of life and work on Tyneside and Northumberland in the not so distant past. Wherever you place it – the oldest building in Walbottle, some remnant of Armstrong’s factory or, perhaps best of all on the walls of the new Centre for the Children’s Book, I have no doubt he deserves it.

(Jim Mackenzie - Newcastle "Evening Chronicle" on June 18th, 2003 - one hundred years on.)

Sea Change

It’s always such a pleasure (and to a certain extent a relief) to come across a new author for children whom I can recommend without hesitation to other readers. Of course, Richard Armstrong, born in 1903, is not really a new author. His writing career appears to start in 1943 and lasts until 1977. His most famous book is “Sea Change” published in 1948 and it won the Carnegie Medal. For me this is entirely acceptable for I didn’t know he had gained this award when I read the book and all the time I was thinking “This book deserves to win a prize”.

“Sea Change” is concerned with a journey which is carried out by a cargo ship between Liverpool and the main islands of the West Indies. The central character is a young apprentice, Cam Renton, who has reached a turning point in his life. Instead of being given a chance to train in navigation and to develop the skills needed to be an officer he spends all his time on dull jobs liking chipping rust and cleaning brass.

He confronts the First Mate of the Langdale, his new ship, and tries to ensure that this latest voyage will be different. Andy, the Mate, proves to be a remarkable character and the story is about how the officer and the apprentice gradually come to terms with their relationship. It is a story about growing up and understanding the demands of your career and the people you must work with. Each personality on board the Langdale gradually becomes familiar to us; each task performed by ordinary seamen in the course of their daily duties is made vivid and real. Armstrong makes us realise that the intricacies of stowing the cargo in the different holds is an intellectual problem that is both daunting and fascinating

. I have read and enjoyed the work of other authors sea-going stories for children. The names of Percy F. Westerman, Douglas Duff and Arthur Catherall spring to mind. Not one of them comes near what is achieved by Richard Armstrong. The perils of a fire in a bunker, rescuing a derelict and facing a hurricane are familiar ploys in this sort of story. Armstrong handles them all with consummate skill and achieves total conviction. However, the depth of the characterisation that has preceded these crises ensures that we care far more about the people involved than we do with those created by other writers.

. I have read and enjoyed the work of other authors sea-going stories for children. The names of Percy F. Westerman, Douglas Duff and Arthur Catherall spring to mind. Not one of them comes near what is achieved by Richard Armstrong. The perils of a fire in a bunker, rescuing a derelict and facing a hurricane are familiar ploys in this sort of story. Armstrong handles them all with consummate skill and achieves total conviction. However, the depth of the characterisation that has preceded these crises ensures that we care far more about the people involved than we do with those created by other writers.

The dust-jacket unashamedly entitles this “A Story for Boys” and perhaps this is true. However, good writing is good writing. For the first time I feel that I understand what my father (First Mate on Merchant Ships out of Liverpool to Brazil and Argentina) was facing when he discussed the problems of stowing a cargo. Naturally I also respond to the fact that this book was written in the year that I was born. “Whinstone Drift” and “Sabotage at the Forge” are two other Armstrong books that I have enjoyed and there are several more to come. He was clearly a very worthy winner of the premier children’s literature prize.

Storm Path (Blurb)

Richard Armstrong is a novelist whose themes penetrate deeper than the surface narration of his story. While outwardly conveing the excitement and hazards of a hurricane at sea, this new novel by the anchor of Sailor’ Luck is really concerned with the conflict between man's need to conform, and his urge to be individual, to diversify lest he perish. The author says he had in mind the intense loneliness often inherent in the human situation and that the storm symbolises the H-bomb, the space-race, the cold-war or any of the controversial issues that bedevil our times.

A ship receives warning of a hurricane, the path of which may or may not cross her course. Prudence dictates avoiding action; but expediency persuades the Master to stand on. The Mate thinks this decision is wrong (though in the beginning he is not at all sure where he stands in relation to the error. As the storm develops, however, so does his conviction that the Master is needlessly hazarding the ship and the lives of her people for his own selfish ends and personal aggrandizement and must be stopped at any cost. Right or wrong, he seeks confirmation, approbation, allies, even reassurance but finds instead blind-folly, self-interest, self-indulgence, plain cowardice and minds firmly shuttered against him. In the end he is completely isolated and accepts the role of tragic-hero, but fluffs it. This is a brilliant piece of character study. There are intensely moving scenes in it and some of savage comedy. It builds up in an atmosphere of brooding danger to an explosive climax and the author's name and reputation guarantee the authenticity of incident and background.

Storm Path (Blurb)

Richard Armstrong is a novelist whose themes penetrate deeper than the surface narration of his story. While outwardly conveing the excitement and hazards of a hurricane at sea, this new novel by the anchor of Sailor’ Luck is really concerned with the conflict between man's need to conform, and his urge to be individual, to diversify lest he perish. The author says he had in mind the intense loneliness often inherent in the human situation and that the storm symbolises the H-bomb, the space-race, the cold-war or any of the controversial issues that bedevil our times.

A ship receives warning of a hurricane, the path of which may or may not cross her course. Prudence dictates avoiding action; but expediency persuades the Master to stand on. The Mate thinks this decision is wrong (though in the beginning he is not at all sure where he stands in relation to the error. As the storm develops, however, so does his conviction that the Master is needlessly hazarding the ship and the lives of her people for his own selfish ends and personal aggrandizement and must be stopped at any cost. Right or wrong, he seeks confirmation, approbation, allies, even reassurance but finds instead blind-folly, self-interest, self-indulgence, plain cowardice and minds firmly shuttered against him. In the end he is completely isolated and accepts the role of tragic-hero, but fluffs it. This is a brilliant piece of character study. There are intensely moving scenes in it and some of savage comedy. It builds up in an atmosphere of brooding danger to an explosive climax and the author's name and reputation guarantee the authenticity of incident and background.

Horseshoe Reef (Blurb)

The mystery that was Trull Island

Two merchant navy apprentices in their third year are washed ashore on the island of Trull when the tramp steamer Melissa is wrecked near what they believe to be the Gannet Rock Light. They are given food and shelter by the Maddock family in whose decaying mansion they settle down to wait for the weather to ease and allow their return to the mainland. The Haddocks, from Mark the eldest, with his high wing collar and deep, gravelly voice, down to the girl Agnes who has a passion for stories about South America, are an odd lot; none of them more so than Aunt Jessica, sour as a green lemon and with an edge to her tongue like a rusty bucket; and the lonely island is a wild, dramatic place. But when the wind goes down and the departure of the boys is delayed by old Mark on one pretext after another, the oddness becomes sinister and the island a trap within which they are suddenly confronted with a grave responsibility. Meeting and carrying this burden is a severe test of character. It reveals their fears and weaknesses, but it also brings out the best m them; their courage and unselfishness, their ingenuity and the budding seaman's flair for improvisation. How they do it is part of a first-rate sea story which is exciting and absorbing from beginning to end.

The Secret Sea (Blurb)

Antarctic whaling is the toughest job left on earth. Thor Krogan, coming of a long line of whalemen, was born to it, and this is his own account of the first expedition he made into that desolate waste of berg, pack-ice and blizzard which is the Southern Ocean. The expedition, commanded by Thor's uncle, Captain Henrik Krogan, consisted of the factory ship, Orion, a tanker, a tender or store-ship and seven catchers. It was a bad season with whales hard to find, and to ensure the success of the expedition and preserve his reputation as a leader, Uncle Krogan headed through the pack-ice for a huge area of open water between it and the Great Ice Barrier where he knew the big blue whales and finbacks seek their food at such times. This is the secret sea of the title, and in the story that follows we learn what befell them there, coming close to Uncle Krogan, Thorsen the flenser and Gorskoy the catcher skipper, and getting some idea of what makes such characters tick. Like all whalemen they are memorable and rather larger than life. Told with authoritative realism against a vividly detailed background of whales, whalemen and the whaling industry, this is a story of blood and ice; of wild hope and grim despair; of little triumphs and final disaster.

It unfolds with all the excitement, action and narrative skill that first brought Richard Armstrong wide recognition and the Carnegie Medal with Sea Change, followed later by the New York Herald Tribune prize for Danger Rock; qualities that have earned him a leading place among writers on ships and the sea.

'Only a deep-sea sailor could produce a book as exciting and informative.' northern echo.

The Lost Ship (blurb)

Shorty, galley-boy in the tanker Ta/ara, and Nick, apprentice in the same ship, both aged seventeen, are the heroes of this sea story. Shorty is crazy to become a 'real sailor' instead of spending his time peeling potatoes. In a moment of showing off, Shorty falls overboard and Nick, in an attempt to save his friend, is pulled overboard too. The Ta/ara crew do not see the accident, and the tanker steams ahead leaving them in mid ocean.

By luck they are picked up by a passing schooner, the Scud, only to find themselves involved in a sinister voyage, the secret of which they gradually unravel. How they solve the mystery and outwit the crooks and in doing so learn to become ' real sailors' is the subject of another exciting yarn in the Richard Armstrong tradition, told with all the mastery of the technical side of sailing-ships for which the author is justly renowned.

The Albatross (blurb)

Illustrated by Graham Humphreys

A life raft is found bobbing about in the sea—its sole occupant a young man suffering from exposure and shock. Judd is one of the four apprentice seamen who sailed together in a British tanker, taking freshwater supplies to earthquake-stricken San Fernando. Gradually Judd's incredible story is pieced together; it is a tale of adventure and conflict., of priceless treasure and a runaway voyage in a stolen ketch, the Albatross. The prospect of such wealth has a terrible effect on the four shipmates-—and the story of what became of them, and how Judd came to be alone in a drifting raft in the middle of the ocean, makes a gripping adventure story.

Like The Mutineers which preceded it, Richard Armstrong's new book describes a starkly real conflict of personalities under extreme pressure. The tense drama develops with relentless logic from the first high-spirited adventure to a very bitter end. Against a setting of wind, wave and sun, Armstrong presents, as always, some strongly individual portraits; it is clear that, in his books as in real life, this writer has the knack of establishing direct contact with young people.

The Mutineers (Blurb)

Illustrations and wrapper drawing by Gareth Floyd

This is one of the most original stories for boys to come from the pen of Richard Armstrong. A group of boys around sixteen years of age, and emigrating to Australia under a training scheme, are just bored with the voyage. After a noisy party they hold the captain and the officers at gun point and take over the ship for ' kicks'. Then, realizing that they have let a joke go too far, fifteen of them escape in one of the boats.

Chick, who has the knack of putting first things first, is chosen as leader, and shows his judgment and presence of mind. It is thanks to him that search parties fail to find them. But he has used violence to assert his authority and he continues to feed his growing greed for power by allowing no opposition. Bo-bo, the brightest of the other boys, is not strong enough to btand up to Chick alone, and Stubby, who might have been a rival, is too anxious to be independent at all costs.

The island paradise is never, in fact, the place of freedom they had imagined it might be. Conflicts build up to an almost unbearable tension, focused upon the frightening stone images which dominate part of the island, and which Chick is obsessed with destroying. Nothing, it seems, can avert the final catastrophe. . . .

Chick, who has the knack of putting first things first, is chosen as leader, and shows his judgment and presence of mind. It is thanks to him that search parties fail to find them. But he has used violence to assert his authority and he continues to feed his growing greed for power by allowing no opposition. Bo-bo, the brightest of the other boys, is not strong enough to btand up to Chick alone, and Stubby, who might have been a rival, is too anxious to be independent at all costs.

The island paradise is never, in fact, the place of freedom they had imagined it might be. Conflicts build up to an almost unbearable tension, focused upon the frightening stone images which dominate part of the island, and which Chick is obsessed with destroying. Nothing, it seems, can avert the final catastrophe. . . .

Out of the Shallows

Boy into Shipmate (Blurb)

Archie Anscombe is sixteen years old when he arrives at Cardiff docks to board the s.s. Limpopo as a greenhorn apprentice. For as long as he can remember he has been fascinated by the sea and ships, though having lived high up among the mountains of the Lake District he has never before seen a ship or set foot in a seaport. Brimful of enthusiasm and brave ideas of proving his seamanship and courage, sensitive and of deep feeling, he is bitterly disappointed by the Limpopo and everything connected with her. Ugly beyond belief, shrouded in coal dust, dirt, rubbish and confusion everywhere, she could hardly be more unlike his dreams of white paint and shining brass. And his fellow apprentices are just as shattering- Jake Blyth the senior apprentice, Cornforth and Ironside, From now until the end of their first voyage, many weeks later, Archie carries a chip on his shoulder, and this story tells of his real character and his development into a good shipmate.

Strong, clear-cut characterization and a straightforward plot make this story very readable and entirely satisfying; it is to be recommended with enthusiasm for its manly and inspiring qualities.